Dynamic Systems Modeling in Psychology

What is a dynamic system? Why are they interesting? How do we take bits of the bumbling buzzing confusion around us and pack them into a statistical model of change to make nuanced predictions and test interesting hypotheses about ‘stuff that happens’ so we can better adjust the buzzing confusion to our tastes? I’m turning the class I recently taught into some blog posts, so for some of my opinion, not intended as rigorous philosophy of science / statistics, but as a start to thinking about systems modelling, read on…

Precise definitions can be troublesome, but in general most things psychologists are interested in can be thought of as dynamic systems, but often just a single instant in the time course of the system is focused on, using cross-sectional data. A dynamic systems model can then be thought of as a representation of how a system changes depending on the various parts of the system and various inputs.

Simplest model of change / ‘dynamics’?

In a very loose sense, we can sometimes think of the humble t-test as a model of change – for example:

- Does ice cream make people happy?

- Take 2 groups of subjects, experimental and control.

- Give experimental group ice cream, control group nothing.

- After some time, ask about happiness.

Such an experiment can give us a precise estimate of the average effect on measured happiness (i.e. some kind of affect / satisfaction / wellbeing variable) for the sample, in a specific context, a specific length of time after the ‘treatment’. On it’s own, this piece of knowledge is useless, as the context is unlikely to be exactly repeated, and anyway being happier at one brief moment when answering a survey question is not very useful. Only under assumptions of some kind of smoothness and regularity in the universe does such knowledge become useful – we can start to think that similar people, in similar circumstances, may exhibit similar effects. Such assumptions of regularity are necessary for any form of knowledge and we are so familiar with such generalisation processes that we often don’t notice – but a critical part of this process is at least having a rough estimate of how far we can generalise. Psychology has a colourful history of cute studies, neat p values and vague / implicit assumptions leading to apparently profound effects that are not so profound in reality. To properly consider the usefulness of ice cream as a happiness treatment, or to leverage the ice cream treatment to better understand wellbeing constructs, we need to embed this new knowledge in the broader system we’re interested in.

Perhaps a little more nuance is needed?

When do people become happier?

For how long?

What does happy really mean in this case? (e.g. what might the corresponding up or downstream effects look like?)

Does the effect change with temperature, flavour, amount, age,…?

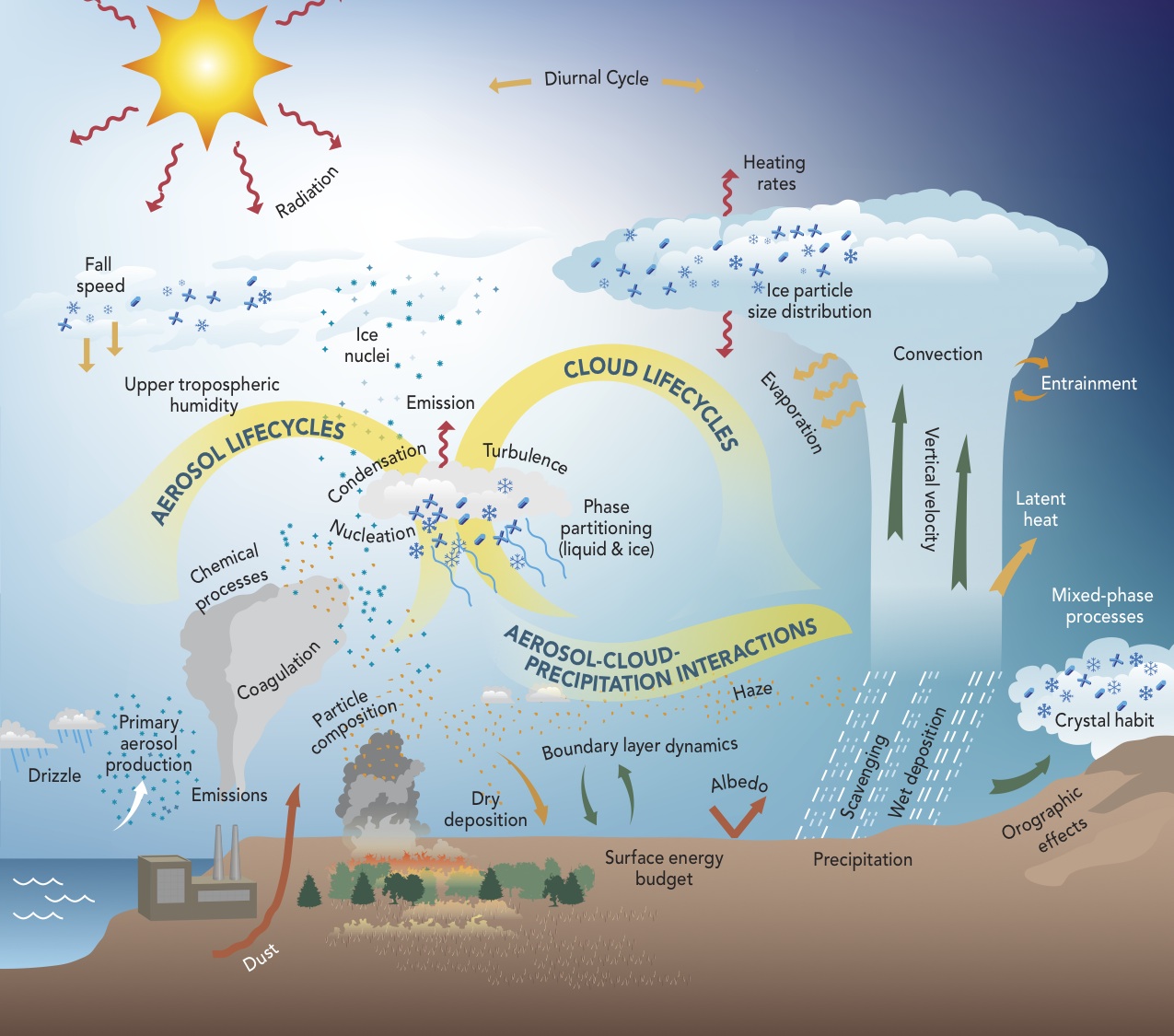

Once we add in a few extra pieces, we start to get more interesting models that can tell us what may happen in a broader range of circumstances, and allow new knowledge to be embedded more easily… something like this maybe?

- Ok, in most cases psychology is still a long from such models. But it’s a nice visual representation of a serious dynamic system model - multiple interacting factors that each play a role in how all the other bits change. Moving slowly in such a direction would represent useful progress, I think.

Why ‘time’ and ‘dynamics’ ?

Why should we care about how a system develops over time, specifically, isn’t time just like any other variable we could decide to be interested in? We could also develop elaborate models for how a system changes in response to loud noise, or being poked with different size sticks.

The interesting thing about ‘time’ is not that we’re specifically interested in the passing of time itself, but that it basically serves as a proxy for ‘all the stuff in the universe that tends to happen’. So you eat the ice cream, start digesting, chemicals start bouncing around a little differently inside you, behaviour changes slightly, other people respond a little differently, and you continue experiencing more of the ‘stuff of the universe happening near you’. So when we create a model for how something changes over time, this is then some sort of general model for how this thing tends to change when we don’t do anything specific, except the initial input.

Time is also a critical element with respect to causal chains – a change in one thing leads to a different thing changing, which in turn leads to yet another thing changing. Mediation is a popular concept in psychology, but in many cases somewhat incoherent without a notion of time passing, and a question that should then arise is how the different processes look at different times after an initial change. For example, we could be interested in the mediating role of exercise habits on peoples fitness. Intervening on peoples habits and checking fitness a day later is likely quite ineffective, but we can measure the change in habits and build / estimate a model for how this change in habits translates into change in fitness, conditional on the passing of time and any other variables we are interested in (e.g. baseline fitness, motivation to change habits, etc).

We could of course ignore time in the model, test at a specific time point, hope that neither too much nor too little time had passed, and claim an effect – but models that consider the temporal development are far more useful for both predictions in applied contexts, and for incorporating new knowledge. In both cases this is because the temporal model applies to a time span, rather than a specific instant. Prediction or incorporating new knowledge based on a model for a single point in time (i.e. not dynamic) to a different point in time requires entirely untested assumptions about the time course – if the dynamic model is developed and tested at all sensibly, it should outperform such assumptions!

Dynamic systems example uses - non psychology:

In a very general sense, models of how things change are successful in many fields. A few examples:

Weather and climate

Finance

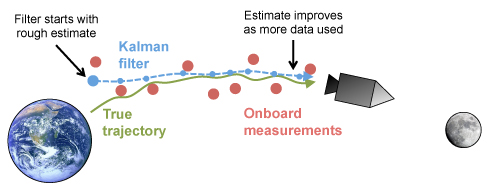

Landing on the moon

What happens when we shine two lasers at each other?

Dynamic systems example uses - Psychology

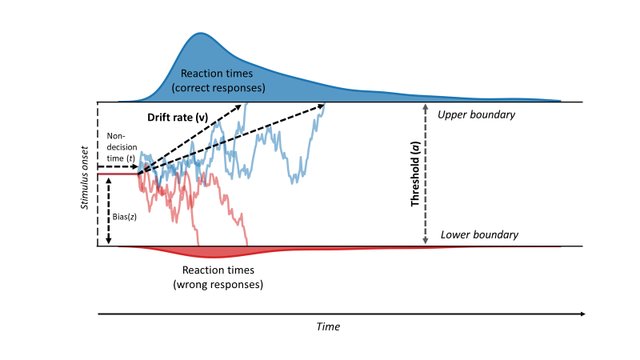

Some models of decision making treat the decision process as a simple dynamic system

Image source: Vinding, M., Lindeløv, J. K., Xiao, Y., Chan, R. C., & Sørensen, T. A. (2018). Volition in Prospective Memory: evidence against differences in recalling free and fixed delayed intentions.

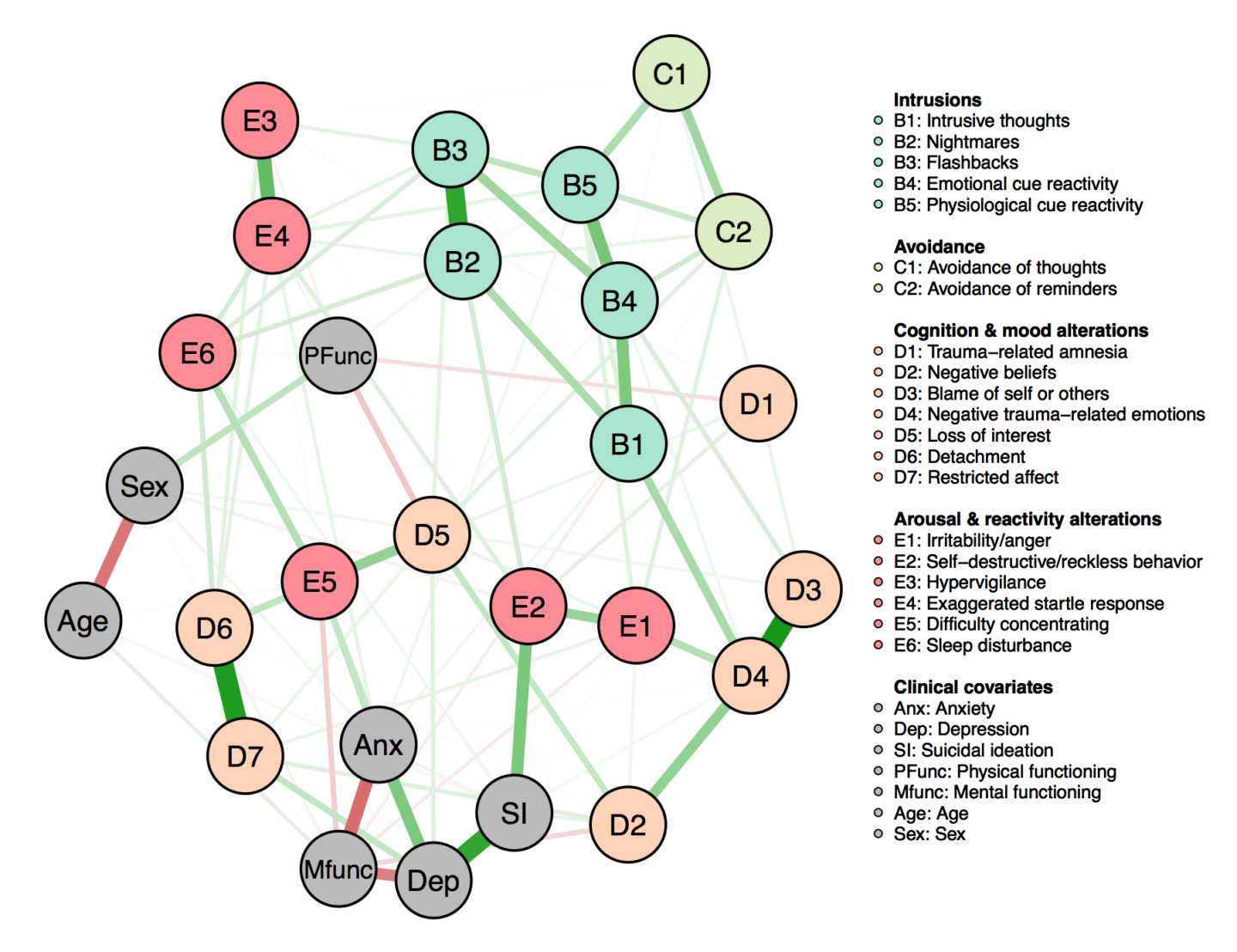

Image source: Vinding, M., Lindeløv, J. K., Xiao, Y., Chan, R. C., & Sørensen, T. A. (2018). Volition in Prospective Memory: evidence against differences in recalling free and fixed delayed intentions.Interest in psychopathology as networks of symptoms has grown a lot in recent years, people are starting to put the pieces together to consider them as symptom (and other feature) networks evolving in time.

Image source: Armour, C., Fried, E. I., Deserno, M. K., Tsai, J., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). A network analysis of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and correlates in US military veterans. Journal of anxiety disorders, 45, 49-59.

Image source: Armour, C., Fried, E. I., Deserno, M. K., Tsai, J., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2017). A network analysis of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and correlates in US military veterans. Journal of anxiety disorders, 45, 49-59.In general there is plenty of history of thinking in a dynamic systems framework.in psychology..

But limited serious applications - probably due to data scarcity, computational difficulty, training…

Possibilities growing rapidly with explosion of data in recent years.

Forecasting

Dynamic systems approaches provide excellent scope for predictions of the future. Such predictions could be based on:

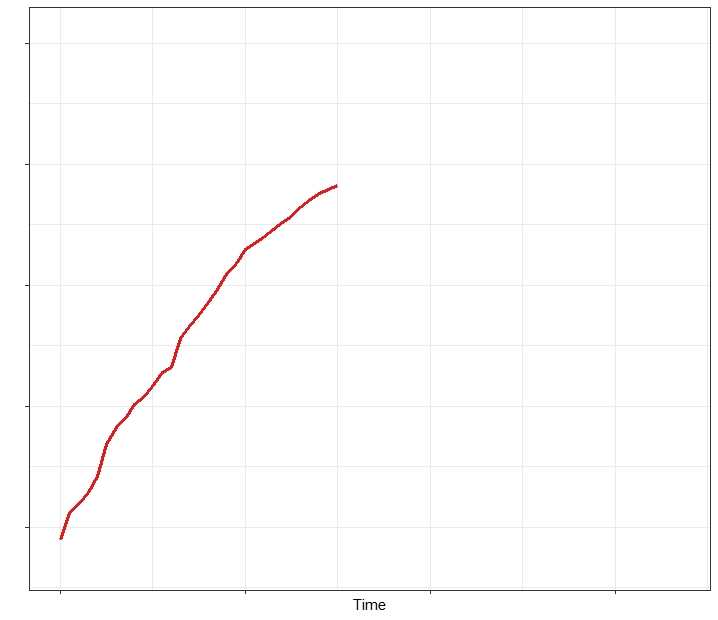

Earlier time points of the specific subject of interest – where do we think the red line will go?

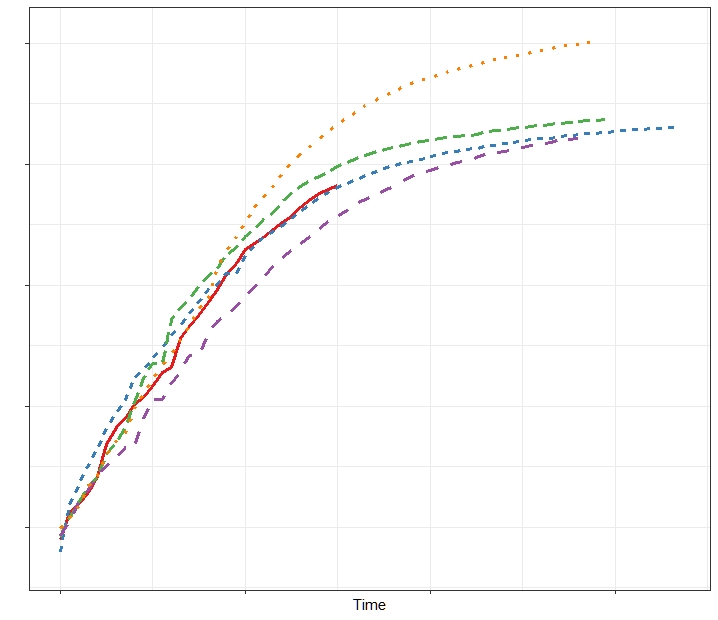

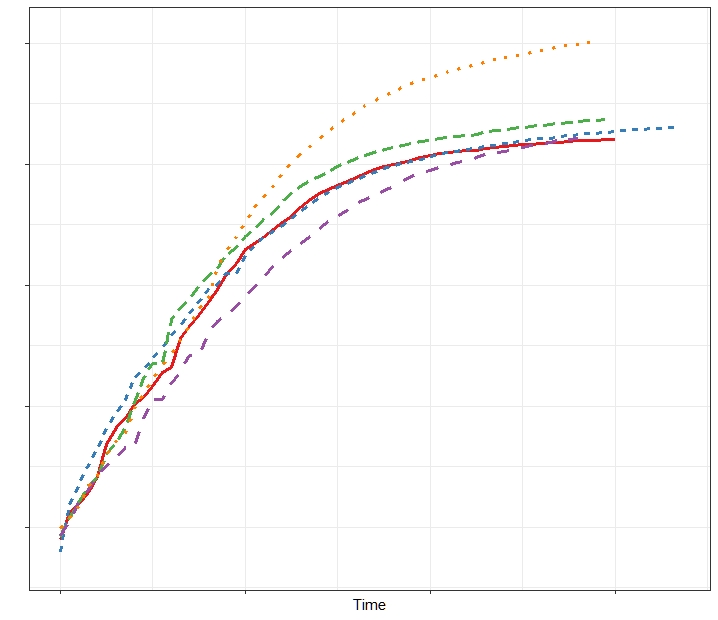

But in psychology, given that there are always similarities between people (compared to say, a person and a block of cheese), we can also leverage knowledge of how other subjects behave – in this case we are probably more confident of where the red line will go now.

Such knowledge of other subjects behaviour, and a specific subjects past, can lead to improved predictions of the future.

Different levels of explanation.

In order to build useful models of how systems we are interested in change, the aspects of the system need to be modeled at an appropriate level. While it is not always straightforward to determine what this level should be, and this may change over time with changing knowledge, I’d suggest that scientific constructs do useful work when either: They represent (at least approximately) something we care about in and of itself, as for instance with things like satisfaction, hunger, pain; or they fit somewhere in our tangled web of knowledge, eventually connecting to things we care about. If we’re interested in the feeling of wellbeing and comfort provided by physical contact with a loved one, we could conceivably model this (some time in the future!) based on an extremely large model involving fundamental particles, but including higher level constructs like ‘people’ will likely offer a much more tractable model, easier to understand and develop further. Perhaps at some level of model richness, brain structures become useful, as do perhaps social conditions.

Another aspect of the ‘level’ of a construct is that of the time scale – quite some debate occurred as to whether short term transient states like a sunny day influenced measures of wellbeing. One way out of such worries is to acknowledge that yes, there are likely to be a range of short term influences on answers to wellbeing related questions, but most such things can probably also be treated as some form of measurement error / noise when the interest is on the year or decade time scale. If the interest was more on the hourly time scale, then fluctuations at one hour likely are informative for the next hour, so they shouldn’t be treated as measurement error.

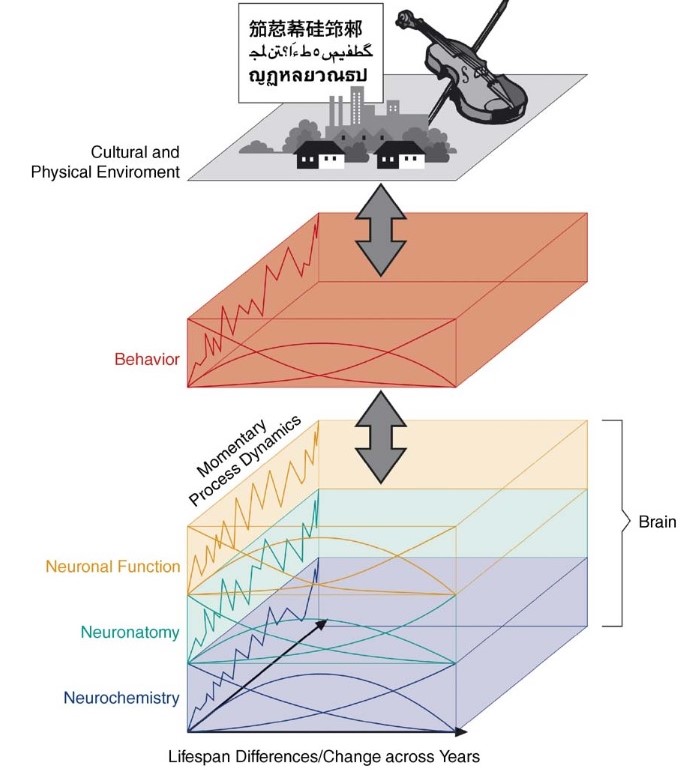

This diagram from Lindenberger, Li, & Bäckman, (2006), neatly demonstrates both the short vs long timescale, and high vs low construct level, for typical cases in developmental psychology / neuroscience.

Statistical modelling

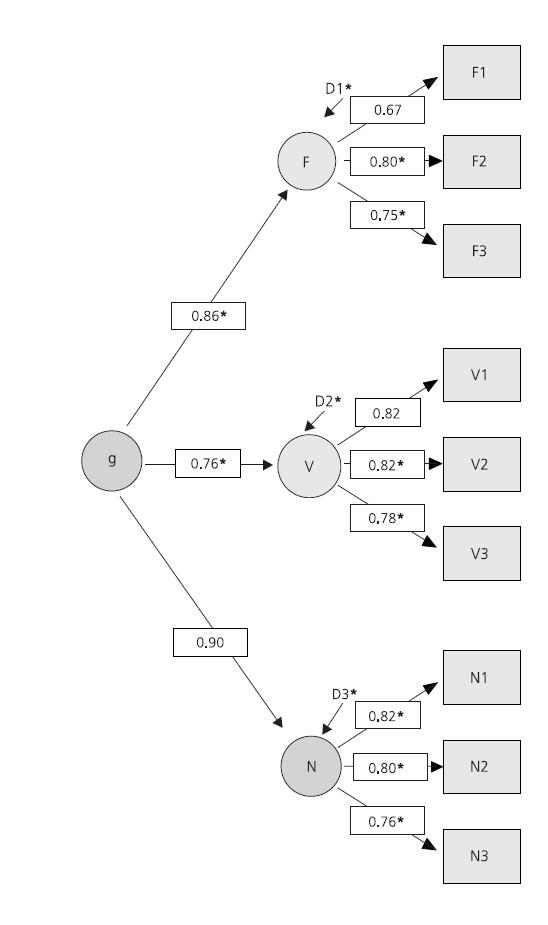

A statistical model usually involves aspects that constitute our actual knowledge and or theory, as well as some auxiliiary aspects that we are willing to assume in order that the model is generalisable and useful. Considering the G factor theory of intelligence, we often end up with something like the following.

Core idea: Intelligence is composed of multiple facets that tend to take on similar values.

Extra assumptions: Factor analysis – linear relationships, Gaussian errors.

Model fit – match between estimated model and reality.

Image source: Süß, H. M., & Beauducel, A. (2015). Modeling the construct validity of the Berlin Intelligence Structure Model. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 32(1), 13-25.

Image source: Süß, H. M., & Beauducel, A. (2015). Modeling the construct validity of the Berlin Intelligence Structure Model. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 32(1), 13-25.

Statistical modelling – what are we doing?

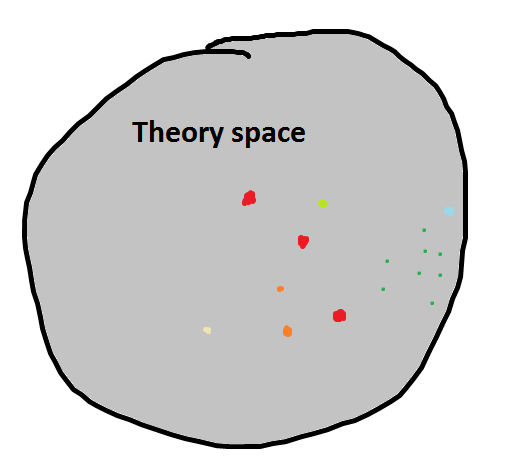

- We want to see how a little piece of the world works – we can think of this ‘piece of the world’ as composed of a range of related variables in some weirdly shaped multidimensional space. I labeled it ‘theory space’ at one point, to represent the idea that there is some reasonable set of elements in the universe that are relevant for the particular thing we are interested in. If we go back to the ice cream and happiness example, this space could obviously contain hunger, age, temperature, time since consumption, quantity / quality consumed, and many other aspects.

- We often start with some very vague ideas about how the aspects in this space are related, goals of modelling can be to test specific ideas and or to improve and quantify our knowledge of the various relations between variables – e.g. the size, time, context, of effects.

- Requires some kind of overall plan – what do we look at, how do we quantify this?

‘True’ space with some observations of some variables:

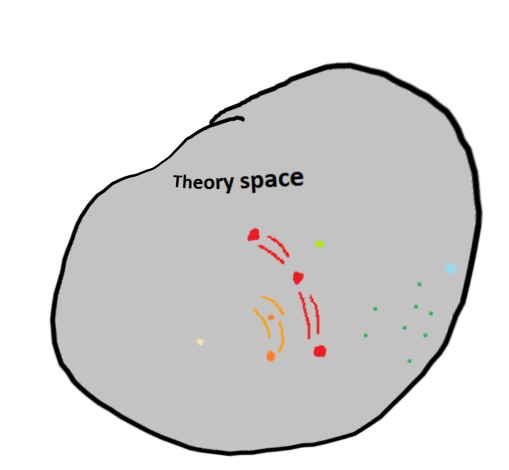

- Model/s – to create a model, we need to decide which aspects of the space we cover, how do we relate the information within?

- A model invariably distorts, and leaves out some aspects of, the ‘true’ system of interest.

- In exchange for this, we can replace mere infinitesimal points in the large space, with links between different regions. (i.e. different values of different variables, that we have not explicitly observed) For instance, in a simple model we might have a linear relationship between ambient temperature and the resulting pleasure from eating. * These ‘links’ (the model!) allow for predictions about what new data would look like and how we might expect variables in a region to be related. As new data comes in, such links / predictions can be tested, and the model refined or rejected. So, once we collect data from Antarctic scientists who’ve been given a load of ice cream, we might improve on the linear model.

- How large / unified should our models be? Depends! More information helps to constrain the system and can provide better predictions and a more integrated pile of knowledge, but it can also make the modelling process, both for the computer and the human, less tractable.

‘Modeled’ space with some aspects dropped, but links between regions / variables in the space:

Next post, I will take a look at ways of representing dynamic systems a little more concretely.